What to consider before adding Markdown to your app

I use Markdown daily. This article was written in it. I've built it into products. I personally like Markdown, but it doesn't belong in every app. If you are considering adding Markdown to your app, I'd like to let you in on the many things you need to think about, spanning UX, performance, security, product, and more.

You might think I am over-thinking in places; that's OK, your mileage may vary. It all depends on your app and context. A key experience for me was building Teamwork Chat in which Markdown is featured front and centre. I took a lot of lessons from that, as well as from apps I've used personally which have perfected some bits and rightly messed up others.

First of all, do you really need to add Markdown at all? If not, I wouldn't bother. It will bring extra code, dependencies, maintenance, a performance impact, and product design conundrums.

Look at who will be using your app, look at your competitors. If users won't get it or they'd much rather have a full-on WYSIWYG / rich-text editor (even if that's down the line), I would avoid Markdown.

You could support a Markdown mode and a rich-text mode, but I wouldn't. It gets messy. What do you store in the database in this case? Can something be created in one mode and edited by someone else in the other? Will you need to convert between formats? How will platforms other than the web display the content? Forget it.

So if you think you'll ever need a WYSIWYG editor, don't add Markdown. You can't control the colour of text with Markdown, for example. Not without any custom add-ons anyway. Never mind if your users will want to be able to copy paste from a Word doc accurately.

Sure, you can make words bold, and so on, but it is controlled;

The overriding design goal for Markdown’s formatting syntax is to make it as readable as possible.

Even if you try to introduce something as boring as multiple empty lines between paragraphs, they will be collapsed to one. If your app has nice default styling, everything wil be managable and readable, at the cost of a little bit of freedom.

How much Markdown do you need?

Who will be using your app? How many would say formatting is important? All or just power users? Don't add it just because you like it. Let's say you go with Markdown only, and you do your best efforts to educate users. In the end, if only a small fraction of users understand and use your Markdown feature, is that a problem? How discoverable does it need to be? I can't answer these questions for you.

When adding Markdown, add the least amount possible. Keep it simple. If only a few little bits like bold and italics are needed, then leave it at that. It will make your life a lot easier in the long run.

Sure, Markdown is nice in that in a lot of cases it enhances what users type. I.e. if someone wrote "I *love* this song", people generally understand that they're emphasizing "love" in that sentence. It makes sense to enhance that with styling and make it italics; I love this song.

Readability, however, is emphasized above all else. A Markdown-formatted document should be publishable as-is, as plain text, without looking like it’s been marked up with tags or formatting instructions. [...]

To this end, Markdown’s syntax is comprised entirely of punctuation characters, which punctuation characters have been carefully chosen so as to look like what they mean. E.g., asterisks around a word actually look like emphasis. Markdown lists look like, well, lists. Even blockquotes look like quoted passages of text, assuming you’ve ever used email.

If something failed or support was removed, it could be shown as "I *love* this song" and no meaning is lost. We could, but it still wouldn't be nice to take away something that was previously supported even if it was an enhancement. Especially for some of the more intricate features of Markdown.

Yeah, there's probably more to Markdown than you realise. I advise you to read the specification(s) from top to bottom. Do you really want people to be able to create large headings? If the feature isn't for long-form text entry, like documents, then I wouldn't think so.

Do you want to support blockquotes? How many nested levels deep? People will abuse this kind of thing.

Do you really want people to be able to create arbitrary tables? Probably not. Should it be possible to insert a horizontal rule?

Do you really want to allow people to insert images by URL? If so, will they be treated like other images in your app? Maybe you generate thumbnails, lazy-load, support opening them in a nice image viewer, etc. If no, you want to block this, then will you support adding GIFs in any other way? Never underestimate the appeal of GIFs.

Should users be able to insert arbitrary HTML in their Markdown input? Yes, that is possible.

If you do not want to support a feature of Markdown, the library you're using might support options to disable it, or you may have to use a custom renderer option for the feature. For example, if you're compiling Markdown to HTML, the library might give you an option to override how links are outputted; e.g. so you can add target="_blank noreferrer" to the anchor.

An alternative way to disable support for a feature would be to override the default handling and return the user's input as is. I'd advise that in general, if you're not supporting something, leave their input untouched. Don't output # Hello as Hello for example.

If you are overriding any default rendering or compilation, I suggest looking at the original source first. We accidentally introduced a vulnerability when changing how links were rendered; the default had some XSS protection built-in.

If you want to add some custom styling, you might get away without touching the Markdown process altogether. For example, if you want to display an icon next to any GitHub links inserted by users in your web app, use a CSS selector like .user-generated-content a[href*=github.com].

Another reason to read the specification is to discover all of the small details. Like what putting double tildes (~~) around a word does, how there is actually in fact multiple ways to apply italics, to create unordered lists, to insert code, to create sequential paragraphs (try two spaces at the end of a line), etc. It's best to know everything you're going to support. No one user has to know everything, but some will push it, you should be covered. You don't want to accidentally break something when you introduce your own custom feature either.

Where and how do I compile it?

Of course there isn't just one specification though and they can be a little ambiguous in places. I'd advise at least looking at CommonMark, GitHub-flavored Markdown, and John Gruber's original specification.

Decide which flavour you're going to support and how much of it. Then if you're compiling on multiple platforms or in multiple languages, make sure each library uses the same specification and rules you've set. It'll only frustrate users otherwise.

Where will you need to compile Markdown? Well, I can't really answer that for you. You should store the Markdown plain text input as is (in your database). This gives you room to make tweaks and add or remove features later. It's always nice to add in a backwards-compatible enhancement.

You could only compile it on the client-side. Newer clients could tweak how it's compiled then later (more easily).

Are you going to send this content in email notifications? Or push notifications? Or anything like that? You'll likely need it to compile it on the backend then too.

If you have native mobile apps, you'll need to set up the compilation on each of those clients correctly as well.

You could compile it exclusively on the backend but if you're being optimistic in your UI, then you'll want to render it immediately (before the API request even finishes). You'll also need it if you're going to offer a preview option.

Whatever you decide, validate, and protect yourself from any vulnerabilities or weird input. Even if it comes in via your API and not the client app you've built.

Luckily, Teamwork Chat used JavaScript everywhere (Vue.js, Node.js, Electron, and the mobile apps were once web apps in a native frame), so we re-used the same Markdown parsing and rendering code across backend, web, desktop, and mobile.

Ordered lists can be painful

One quirk I found annoying was that if someone types "2. Emily and Mike", some libraries will output the list starting at number 1. I.e. "2. Emily and Mike" becomes "1. Emily and Mike". This is a feature of Markdown they've determined (according to the original specification). First of all, it's being interpreted as a list, but there's more to it than that. If you enter the following:

1. Apples

1. Bananas

1. Pears

The output will look like this:

- Apples

- Bananas

- Pears

When writing lists you don't have to worry about getting the numbers correct. If you draft the list then decide to change the order of some items, you won't need to go down through the list tediously correcting number prefixes.

OK cool, but that doesn't change the fact that it's frustrating. Imagine if someone asked "How many people went last night?", you response with "2. Emily and Mike", and "1. Emily and Mike" is shown.

When using a chat app, some people prefer to send one message responses with multiple sentences, whereas as others like to send multiple messages in a flurry. Type, enter, type, enter, type, enter... and so on. Imagine the latter wanted to send the list of fruit above. Since each message would treated as a separate input and compiled independently, it would look like this:

- Apples

- Bananas

- Pears

If HTML was the target language, the output would be:

<ol><li>Apples</li></ol>

<ol><li>Bananas</li></ol>

<ol><li>Pears</li></ol>

Long story short, test your library candidates for this issue, or you could opt out of supporting lists. If you output exactly what users enter, you wouldn't have these problems. Sure, it'll output as a paragraph, not a real list, and you can't style it as a list, but that's probably a fair trade-off.

Forget it, I'm just going to create my own format

Hmm, not so fast. Why create another text-based format? At least some people understand Markdown. You'll probably end up with similar issues anyway. Slack decided to create its own weird markup syntax for example. People need to memorize the keyboard shortcut for the unicode bullet character in order to write an unordered list. Not good.

Where and how should it be rendered?

Even if you've only one client, it's not as simple as running the text through a library and sticking it on the screen. Let's say you have a web app. When the input is submitted, it's compiled to HTML and rendered in full on the screen. What if it's really long? What if it contains a massive image?

Do you need to show it anywhere else? For example, do you need to show a preview or summary of the content anywhere? How will you cap it? Will you collapse it onto one line for the preview? You could insert the full HTML and use CSS but that seems wasteful. You could try to only insert or show the first element, but that could be a table, heading, blockquote, or an image. It's not easy.

What if the result is visually blank? The user could've entered []() for example. What do you do then?

There are also areas where you can't use HTML. For example, if you want to send a push / web notification containing the content, you need to give plain text. What would you do? It depends on your app and users, but you could show the input as is. You could strip out some of the input, leaving only the obvious emphasis marks like asterisks. It's not easy.

This kind of stuff might be worth considering when choosing your Markdown parser.

Nail the text entry and preview UX

How will users enter the Markdown? Will they simply type plain text in a textarea and once submitted, it's compiled and rendered? Is that acceptable for your users? Or should you offer an option to preview the result before submitting?

And or maybe you should give feedback as it's being entered. If a user types*hello* world you could apply italics to "hello" as a hint (via a content-editable textarea or something like that). If it's an entire document that's being edited, maybe the editor is the input, preview, and result view.

Whatever you do, don't change the user's draft input. I'm looking at you, Notion; it does some nice magic stuff, but hiding the asterisks after they're typed is not good. It's more awkward to edit afterwards.

You could support a few light WYSIWYG options. If you select some text and then click the bold button or press the keyboard shortcut, two asterisks could be inserted before and after the highlighted text. You could bold in place then like I said earlier, but as a minimum, the double asterisks must be inserted.

If you're going to visually bold the text, then you must always do this; i.e. even if the text with double asterisks are manually typed or pasted. You need to run your parse and styling code whenever the text in the field changes.

It's worth noting that Slack recently added WYSIWYG controls to its message form and got a lot of heat for it. To be fair though, it wasn't just that people didn't like the extra icons being there. It's that entering text as they knew it was broken. E.g. entering text before an inline codespan. In the end, Slack added a setting to disable the new rich-text editor.

Finally, make sure your input styling logic matches how the compiled output is rendered after the form is submitted. Otherwise, what's the point?

Leveraging Markdown for product features

Markdown has a lot figured out for you. It's a good base. You can even exploit some of its feature to easily add product features of your own. For example, with Teamwork Chat, we quickly added a quote option next to each message which did the following:

- Inserts a

>(Markdown's block quote token) at the end of the message form (preceeded by a couple of newlines if the textarea wasn't empty). - Copies the original Markdown input of that message into the message form.

- Inserts two newlines at the end.

- Focuses the textarea, putting the cursor at the very end.

This allowed us to quickly release the feature. Of course, it has it's drawbacks like:

- The system can't distinguish between when someone clicks that button and when someone manually types a quote.

- There isn't any link to the original message.

- If the original is edited, the quote isn't. This could be seen as a feature to some.

- It's hard to tell if a quote is accurate.

- The quoted message could be huge. Although, this could be truncated behind a UI control I guess, but there are the same problems of where to stop, what if there's a huge image, etc.

It is nice though that you can quickly get something like this out there, measure, and grow the app organically based on engagement and feedback. Keep an eye on the alternative though; if few use the current quick solution, that doesn't mean they don't want it done well. Watch out for survivorship bias.

Similarly, you can get a lot out of the box with images, code blocks, and more. Again, this will only get you so far though.

@mentions and other custom features

You can always add custom features in as well as supporting Markdown. In my mind, there's Markdown rendering and there's Markdown parsing. Rendering is taking the input and showing it on screen. Parsing allows you to traverse the Markdown input so you can pull out any important information, without a focus on the result, visuals, or anything like that. These tasks might not always be done together or by the same part of your system, and tailoring the two independently can allow for some nice gains.

Let's say you want to support @mentions in comments. You might render the output on the client-side, including styling any valid @mentions (autolinking to a profile page, etc). You'll want to parse the @mentions on the server-side to decide who should receive an email, web, or push notification.

You could manually parse @mentions from the input, ignoring the fact that it's Markdown. This will be a little awkward though. You probably only want to support @mentions in some Markdown elements and not others;

- @mentions in code blocks should be completely ignored. They shouldn't get any visual treatments, be parsed, or trigger notifications.

- @mentions in comments should probably not trigger notifications but they should be visual emphasized.

So your parsing needs to be Markdown-aware. You could prime your Markdown library for a custom parse flow, overwriting default compilation methods to instead look through the string for @mentions. You would do only need to do this for some elements and not others as some are lower-level than others and some should be ignored as I said.

Alternatively, you could use a flexible library like markdown-it which has a lot of plugins out there for enabling extra features on top of Markdown, like @mentions, automatic heading anchors, custom token handling, etc. I use it for this static blog right now, but I can't say I've used it in a production web app.

If you're going to support @mentions, you should autocomplete @mentions in a popover, but as I said earlier about WYSIYG options, don't just focus on UI controls. If someone manually enters an @mention, pastes one in, if inserting content auto-saved in localStorage, or someone edits existing content, @mentions should behave the same.

Of course, any time you add any custom feature, be aware of the performance and maintenance overhead it introduces. @mentions in particular are more work than you'd expect, between Markdown-aware parsing, the order of autocomplete options (e.g. relvant, recency, misspelling), placing the popover over where they're typing can be expensive (at least on the web), the backend processing, routing of notifications, and so on.

Code and syntax highlighting

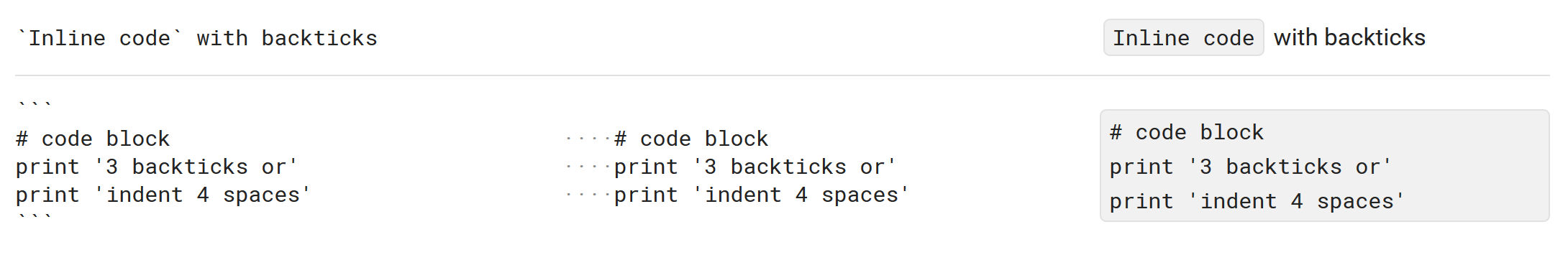

Markdown allows you to enter code. Either via inline code spans in paragraphs or in multi-line code blocks. At a minimum, all Markdown inside these delimiters should be ignored. It's an escape hatch.

Code examples in CommonMark's reference

It should also look different. Typically, a monospaced typeface is used, a gray background is applied, and if there are any long lines, it overflows horizontally instead of wrapping.

Should you run a syntax highlighter library on the output too? In my opinion, yeah, probably. Typically, apps that support Markdown and support entering code in Markdown, highlight the syntax in the rendered result. It can feela bit disappointing when this is left out.

It does have a performance impact though. Let's say you render 40 comments on the screen. You then need to look over all of them on the client-side to see if they contain code (syntax highlighters are typically client-side in my experience) and then run the highlighter to style it.

If you're not going to support it, maybe you shouldn't support code blocks at all? Although, having an escape hatch is handy. You could do what some apps do and support a separate method for adding code snippets. This could allow for extra features, plus it'll make it easier to detect when to run the syntax highlighter.

The future is fast(er)

Performance should be a factor when choosing your Markdown compiler. How much of a factor it should be depends on your usage. How many strings will need to compiled and how often? How much text? Markdown parsing is not the quickest of tasks, in client-side JavaScript at least.

Some libraries are very careful about performance. Check the project readme for statistics or benchmarks against other libraries. Some have tests to make sure compiling a certain string always completes in less than N milliseconds. Keep it in mind yourself when adding any custom functionality (more about this later).

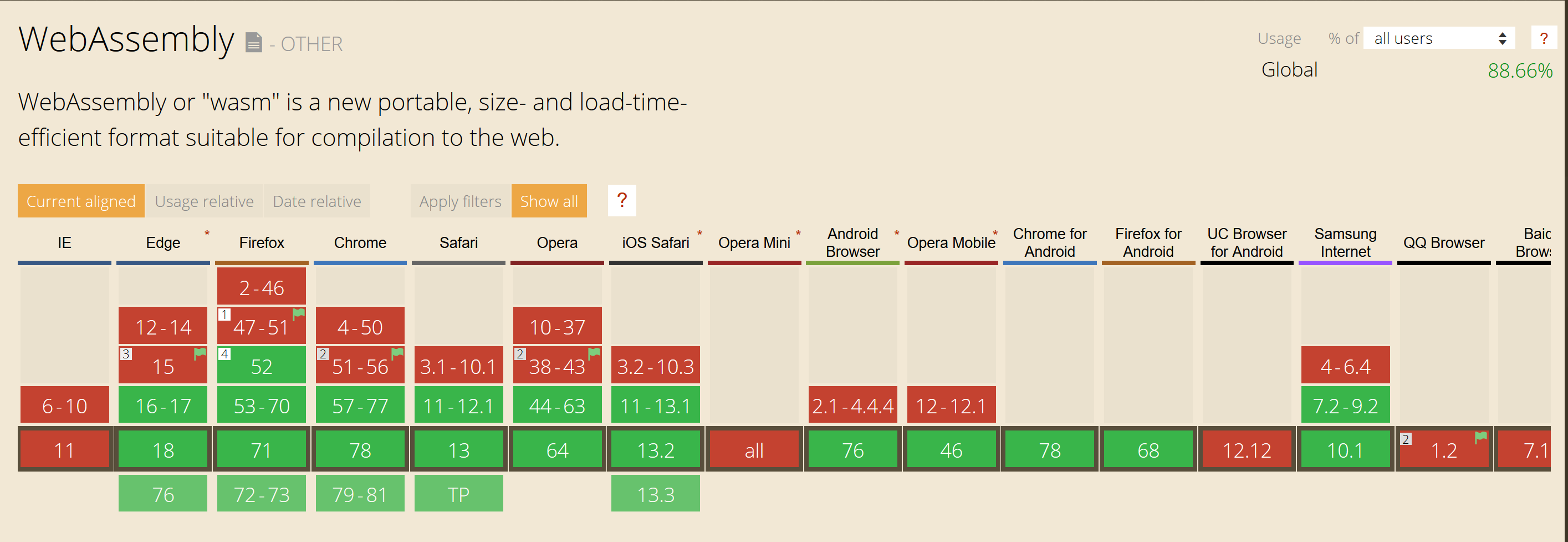

I was lucky enough to attend Patrick Hamann's great 'WebAssembly – To the browser and beyond!' talk at the performance.now() conference this year. Forgive my over-simplification, but WebAssembly (WASM) is a compact binary instruction format, like a portable representation of low-level languages. A host language (like Rust) is compiled down to WASM, which can then be executed on any architecture (via a WASM virtual machine) very efficiently.

The current browser support for WebAssembly.

WASM modules can be called via brower APIs, and it's rapid. Instructions can even begin executing before the file is finished downloading.

WASM will have a massive impact on programming in general, but what has this got to do with Markdown? Well, eventually it will be possible to compile a lot of other languages to WASM and to call WASM modules from a lot of languages. It will be possible to run it on the client, server, and edge. This could allow us to call a single Markdown compiler from any language or platform in our app, giving us the utmost consistency and performance.

Work has already begun on this. In his talk, Patrick mentions this WASM Markdown demo which uses the pulldown-cmark Rust library to compile the Markdown. More recently, Rasmus Andersson released the wasm-markdown module which is based on the md4c Markdown parser (written in C). Check out the demo to see how incredibly fast it is.

I could be wrong but there could be an issue around those custom compilation callbacks / hooks I mentioned earlier. How can I pass a custom function to override how links are compiled? Especially if the function needs to be created at runtime as it depends on user settings or input. Maybe it'll be possible yet slow, or maybe it'll be fine. If there are any WASM experts reading this, let me know please.

Summary

- Listen to the customer and actually solve their problem, properly.

- Don't add Markdown unless you really need to.

- Don't create your own text-formatting standard.

- Pick your flavour and stick to it.

- Keep it simple; disable features.

- Be consistent between input, output, platforms and devices.

- Validate and protect yourself against XSS.

- Consider where and how the content needs to be displayed.

- Keep an eye on performance. WebAssembly will be a huge win for Markdown.

- Nail the text entry and preview UX.

- Leave draft input untouched.

- Don't just focus on client-side controls, parse user input every time it changes.

- Leverage Markdown in order to quickly ship product features but know it will only get you so far.

- It's easy to add custom features but you might need to separate parsing and rendering methods.

- Highlight syntax if you accept code.

- Make it discoverable and educate.