Under the hood of a hybrid (app)

It has been about a year since we had A peek under the hood of Teamwork Chat. Since then, we’ve added a few nice features, fixed some bugs, and introduced a couple. You know how it goes. More and more companies are using our app, including some really famous ones. At the time of writing this, over 12 million messages have been sent. Teamwork has grown three times in size, and the Teamwork Chat team with it, thanks to some great hires.

Let’s take a look at some of my predictions from last year’s post;

As NW.js (0.12.0) is basically Chrome (41), we can just put our desktop app on the Web and it will basically just work. That’s a simplification but you get the picture.

Along with our Windows and Mac OS X desktop apps, Teamwork Chat is now available in your favourite Web browser. This was almost as easy as we expected. See Donal’s recent Deploying the Teamwork Chat Web app post for more.

Sure, Teamwork Chat is a mobile-first responsive app, so yes, users could access Teamwork Chat on their phones. This was welcomed with open arms, but did I make any mobile app predictions?

Even further, we should be able to create Android and iOS apps by sticking our app in a WebView. We’re attempting to build a consistent experience across all platforms from the one codebase. It’s not as easy as I make out though; expect more posts to follow up on this.

Yep, and that’s what we’ve done. In this post, I’m going to describe how our Android and iOS apps came to be, lessons we’ve learned along the way, and where we’re headed. Not only in respect to mobile apps, but Teamwork Chat as a whole.

Mobile apps, finally

We released our first internal prototype about a year ago; a mash of Appcelerator and some Web code. It wasn’t as nice as we thought it would be. We would’ve needed to put in a lot more work to make it really usable. We had bigger fish to fry though. After a painful period of trying to maintain it while delivering key features, it was put to one side. We eventually got back to it, starting again from scratch.

Of course, we wanted Android and iOS apps which allowed you to do everything you could already do in Teamwork Chat. Push notifications and being able to share a file to the app were minimum requirements as well. Unlike other apps where you could get away without those, they’re critical for any chat app. We imagined that the least the Teamwork Chat mobile apps could do is allow you to contact someone while on the go and stay in the loop, as well as quickly share a photo you’ve just taken, for example.

Our intention, as much now as it was then, is to have a consistent and familiar experience across all of our apps. Someone should be easily able to start a conversation on one device and carry it on elsewhere.

Reusing our Web app

By this stage, users were crying out for mobile apps. Our plan was to get mobile apps out there and improve on them. We planned to reuse our Web app and see how far we could get. We took ownership of (most of) the app as apposed to our mobile team here at Teamwork. We got a lot of the way for free as we had already fought to maintain (mobile-first) reponsiveness and touch-friendliness throughout. We got an iPad app for free due to the fact our app is responsive. Note: we’ve never used device-orientated breakpoints in our designs.

Now, mobile apps are also considered in every feature from the beginning. Reusing code between our Web, desktop, and mobile apps enables us to fix a bug once and it’s fixed everywhere. As I said in last year’s post, we use Node.js on the server-side, so we have some modules which are used in our Web app, our Mac & Windows desktop apps, our Android & iOS apps, and some services. Imagine that.

It was more difficult than we had anticipated. Debugging was trickier for one, and sure we had made an app that was responsive, but it wasn’t responsible. I wish Teamwork Chat really was mobile-first. We should have worked on mobile apps or at least made the Web version first and used it in mobile Web browsers often. The app was far too bloated, it was doing too much all of the time, and so on. A lot of improvements came from making the mobile apps, which in turn improved every Teamwork Chat client as a result. All Teamwork Chat (mobile, Web, and desktop) apps now load faster, take less time to render, and so on, but we still have work to do.

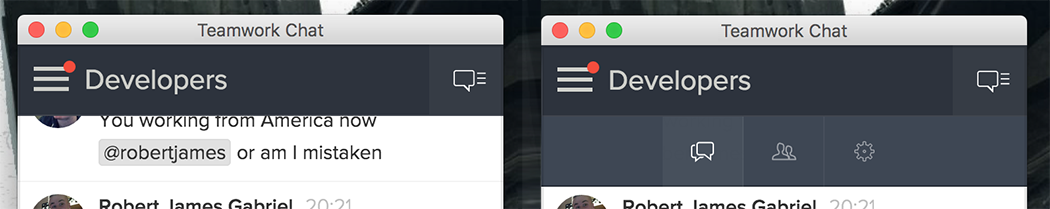

A navigation menu we tweaked.

We forced ourselves to use our mobile apps exclusively; any interaction we made in Teamwork Chat during the day had to be done in the mobile app. This really helped. We completely redesigned some navigation menus, made some tweaks around touch input, and more. Sure, we already designed our app for touch, but how often did we really use a touch laptop or heavily use the app in a mobile Web browser? Well, clearly not enough. So we fine-grained a few things, including the swipe to show or hide the sidebar.

Native wrappers

Enough about the WebView. In this iteration, we decided to drop Appcelerator and go with some native code instead. Sure, this means we’d need two implementations, one in Java and one in Swift, but it’s not so bad. It’s not a lot of code, the end result is better, and it’s what our mobile devs would prefer to work with.

The native “wrappers” need to show our app in a WebView (which is stored locally), handle notifications, and so on. We found a way to communicate between our app, the native side, and vice versa. I must say it was pretty interesting to co-operate with native mobile developers on this. Once we agreed on the events to be sent back and forth, we were adding little touches which made the app feel a lot more native in no time. For example, if you were to tap the back button on Android, an event is sent into the WebView, and we then close whatever’s open, or hide the sidebar, etc.

Notifications are another good example. The native side gives us an access token for the app instance on each launch, we send that off to our API and then send you push notifications based on that. We send metadata like the conversation ID in the push, so if you were to tap on it, the native side of our app would instruct our Web app to open the conversation in question, and voilà.

You can go a step further and clear existing notifications on Android, which is a nice touch. If you were to receive a push notification about a message, but then view it in one of our desktop or Web apps, then the notification would disappear as you’ve already seen the message. When you view a conversation, an event is sent to from your client to ones of our services, and eventually a “silent” (invisible) notification is sent out to your device. Our Java code grabs the conversation ID and clears all associated notifications.

But what about real mobile apps?

OK, fine! Let’s talk about Web versus native for a second. Web apps on mobile have gotten a bad name, unfairly. “Our biggest mistake was betting too much on HTML5” is commonly attributed to Mark Zuckerberg. Even though I don’t think this is actually what Mark said, people have latched onto this. It’s rubbish. Facebook’s HTML5 push wasn’t very successful at that time for a few reasons, one of which was down to process, for example. They had a dedicated mobile team. Mobile was always an afterthought, and it showed. Now they have mobile developers on every team. Mobile developers are involved and mobile apps are considered from beginning of any feature. If it was up to me, Teamwork Chat would eventually have some mobile developers of its own too.

A lot of apps you use are hybrid apps but they don’t announce it due to the stigma involved. The feed you see in the Instagram app, who’re owned by Facebook, is HTML.

We put in the effort to make a responsive app, why not try to flex it? Sure, I’m biased; I want the Web to win and it is possible to do what we had aimed to do. Don’t get me wrong though, fully native apps are the way to go for Teamwork Chat. At the end of this post, I’ll cover what the plans are for our mobile apps and the future of Teamwork Chat in general.

Sharing

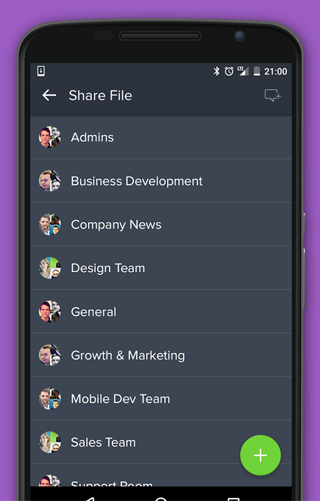

The screen shown when something is shared to our Android app.

Android and iOS diverge when it comes to the concept of sharing. For awhile now on Android, you can easily share anything from one app to another; once you tap the share icon, all apps which can handle files of that type will be shown. Typically, once you select an app, you’re then brought into said app, and how the app handles the rest varies. For example, the Twitter app will show a form to compose a tweet with the image already attached. Once you’re done, you’re still in the app. So we didn’t need to do much on the native side to achieve this. We pass the image data in an event from Java to JavaScript, and show a screen inside the WebView allowing you to choose which conversation to share the file to.

Once the user selects a conversation or decides to create a new one, we attach the image to the message form. Images are just one example though.

These days, the right thing to do on iOS is to have a “share extension.” This is almost like a separate app. It lives completely outside your app. What I mean is that when you decide to share something, a completely iOS-y dialog appears, in which the entire flow is contained, and you stay wherever you were once you’re done. So this is written completely in Swift and solely interacts with our API.

Feature parity

This is something I strongly believe in. I’ll strive to make sure every feature of Teamwork Chat ever released will be released on all platforms and apps at once. There’s nothing worse than seeing a press release for a really cool feature in an app you use, only to realise you’ll have to wait awhile longer than everyone else. You don’t want to alienate your loyal users.

This certainly applies to mobile apps. Everyone, please stop delivering your app to one platform before the other. Don’t punish anyone because of the device they happened to buy.

Yes, this means that I believe every feature should be accessible from anywhere, on any device. It’s 2016, I shouldn’t have to defend this. Nowadays it’s really hard to even define what “mobile” means anyway. Screen size? Hmm not really anymore. Touch? Not unique. On-the-go? No, a lot of real usage happens on the couch. I won’t go on. The lines are blurred.

In order to create an app for everywhere, you must design for touch everywhere and strive for simplicity. On the most narrow screen, you need to decide what’s critical for your users, moving on and up from there.

This comes with some fresh challenges. Releasing both Android and iOS apps at the same time is tough. Especially when there’s internal pressure to release one or the other. It’s hard to convince people at times. We’re users after all, we make stuff to scratch our own itch at Teamwork. I must admit I gave in once or twice, but I’ll continue to fight for it. As it is in general, internal perception is important here.

I wish more people wrote about feature parity, mobile-first workflows, and the transition from something more archaic. It affects the process of delivering an app in a lot of unexpected ways. For example, I remember having to push back when it came to marketing videos, which typically featured iPhones and iOS only. These growing pains are good though.

To make this work, more people need to work together and in parallel to deliver something great together. It doesn’t help that your mobile app needs to be reviewed. Android app submissions may only take up to a day to go through validation at worse, but the Apple review process could be anywhere from a few days to a couple of weeks. Not only is it difficult to align all of the releases, but what if a submission gets rejected?

Living with a mobile app

Working on a mobile app is completely alien to Web developers. If you introduce a bug, you can’t just roll out a quick fix and forget about it. It can take a lot of time to release the fix and you’re not guaranteed every user will even accept the update. Luckily, we were already in this frame of mind as we have desktop apps which follow pretty much the same flow.

Even though we’re used to pushing out desktop app releases, the delay and uncertainty involved here is a pain point. A workaround we’re looking at is updating our app without going through the app store. What I mean is that we ship our mobile app with our Web app inside as usual but when the app is launched, it hits an API or S3, checks for a newer version and downloads it in the background if one exists. Then this version would be used in the WebView on next launch. This would allow us to roll out changes on a whim.

By changes, I mean changes to the WebView only. Anything else will require a proper app store update. Full updates should be done regularly anyway so it doesn’t look we have never released an update. Also, so we can update the changelogs on the app store listing. It would feel weird to put stuff in the changelogs which have been in the app for awhile though. Yes, I’ve been told I’m paying too much attention to changelogs. We could run into the situation where the WebView or native wrapper sends an event which crashes the app if we were to make a breaking change in our event API.

This is interesting though; it makes me wonder about how we update our desktop apps. Maybe we could transition to an update process like this. The jury is still out yet though, the implications of a possible move from NW.js to Electron would need to be taken into account here. You might see a post on this in the future.

Feature flags

We’ve been talking about using proper feature flags for awhile now, but this could be something else which would help us achieve feature parity. The idea would be to put the code for a feature out there on every platform behind a flag. We have this already for tiny things, some code is conditionally ran for just us, etc. When I say “proper features flags” I mean we’d hit an API to get this setting. Once all of the releases are out, we’d enable toggle the feature flag and on next reload or relaunch, the feature would be there.

Teamwork Chat is very much a single page app though, so it would be even better if a feature could be toggled at runtime. For example, we could enable search for everyone and boom, the search icon appears for everyone. This opens the door for progressively rolling stuff out, to certain accounts, to a percentage of our users, as well as A/B testing, and even disabling the feature again if the fan requires some cleaning.

The release

Expecting that we’d be waiting awhile, we submitted our iOS app first. The terrible piece of software that is iTunes Connect gives you the option to release the app immediately once it has been validated, on or past a certain date, as well as a manual release. We opted for a manual release. The plan was that was once we were alerted that the app was ready, we’d submit the Android app, and once that was out, we’d hit the publish button. Note: the Google Play Developer Console (which is awful too) has added a manual release option since then.

Our iOS app was rejected. Argh! We had marketing campaigns ongoing teasing something big, we had to quickly come up with a plan B. We didn’t want to be empty handed when the end of the month came by. Why did it fail? Basically, there was a misunderstanding in what our app was, and who it was targeted at. We promptly submitted an appeal, and even though we knew we were right, we were amazed to see the decision overturned a couple of days later. The Android release took a couple of hours, and that was it, the Teamwork Chat mobile apps were out there. We were ecstatic.

The future

There is definitely room for improvement, I’ll be the first to say it. They could be faster, start up quicker, be less janky, and so on. We’re going to work hard on this. The great thing is that this these efforts will translate into improvements in the Web and desktop apps as well.

We will be making native mobile apps. We have planned to for awhile now. We have some mobile developers in-house dying for a crack at it. Expect a couple of great apps that really feel at home in your OS. One upside to going down the native route is that users can see you care as you’ve tailored an app to their OS. Sure they’ll be distinct, the Android one will have a strong material design feel, but we’ll strive to keep in sync with each other and Teamwork Chat in general when it comes to features as well as the overall experience.

Sure, this means we’ll have fewer eyes on our Web app on a mobile Web browser or narrow screen, but it’s worth it.

Automation and deployment

Right now, our desktop apps need to built on Windows for Windows and on Mac for Mac. This takes time. We’ve added more update channels which compounds the problem. I’d love to automate this. Mobile app builds and deployments could also be automated in a similar fashion. Watch this space.

While we’re on the topic, I’m happy to say we’ve moved from DeployBot (formerly dploy.io) to CodeShip for all continuous integration and deployment. DeployBot wasn’t reliable enough for us. One time I decided to roll back and it deployed the wrong commit. As well as incidents like that, their frequent maintenance windows seemed to always coincide with when we needed them the most.

All of our services are now deployed once we push to master. Same goes for the Web version, but we don’t roll out as often as I’d like. Continuous delivery is a target though, for the desktop apps as well as our Web app. Although, to get there, we need more automated tests. We’ve heavily tested certain critical pieces and at least 85% of new services are covered with tests, but we need more. Especially integration tests for clients, ran in multiple browsers concurrently. This is possible, I’ve done it previously with Selenium Grid, etc., we just haven’t made the time for it yet.

There are also a few tools out there now for testing responsive designs. We could, for example, take screenshots of pages at multiple breakpoints, compare them with the most recent stable ones, and fail the build if the visual diff is too much. Although this might not be a great fit for continuous integration; I’m not sure how it would work if you intentionally introduced a significant visual change. You could disable the test if a certain [skip-resp-tests] exists in the commit message, but what if you accidentally broke something else? Food for thought.

Lessons learned

We haven’t had too many scale-related pains, although we’ve found ourselves making more changes lately to take some load off Teamwork Projects. Our (email and push) notifications service could certainly be more fault tolerant. We’ve made more use of Node.js’ cluster module which allows us to use all of the cores on any given machine, and might yet solve another problem.

As I described in last year’s post, our clients connect directly to our WebSocket servers. This means a server rollout will result in users’ clients temporarily disconnecting (plus each of them hitting the API at the same time to get any messages they’ve missed). We’re going to workaround this by effectively hot reloading via cluster or having a dedicated instance in front of our WebSocket servers with the sole duty of accepting WebSocket connections and load-balancing the events that come over them.

How our services communicate is a bit simplistic in general. We’re going to switch over to RabbitMQ from Redis, re-do a lot of the messaging, and try to remove the dependency on a shared database at the same time.

Fire in the hole

As well as improving areas we’ve neglected, these are some of the bigger higher level features we have coming down the line:

- API

- Bots (prepared third-party bots and a bot API/platform)

- Conversation switcher

- Deeper integrations with Teamwork Desk and Teamwork Projects

- Email improvements

- Independent signup

- Linux desktop app

- More third-party integrations (including cards, bots, etc.)

- Native (Android & iOS) mobile apps

- Noise reduction (do not disturb, muting, notification settings, etc.)

- Opening Teamwork Chat to users outside the owner company

- Search

That’s all folks! We’ll catch up again next year. Feel free to reach out to us at chat@teamwork.com with any API or bot-related ideas or features requests. We’d love to know what you’d expect to see in our API. If you’d like to kick the tires of our hybrid, follow one of the following links:

Pssst! Did you know that Teamwork Chat developers get to do whatever they like after lunch every Friday? Including improving something which annoys them (even in other Teamwork projects), hacking away on a cool open-source project, learning something completely new, or even playing around with fun just for the sake of it. We have ambitious plans, we now have five apps to maintain, and a lot of interesting challenges ahead of us. Come join the crew.